How Lehnert & Landrock’s Haunting North Africa Images Speak to an AI Age

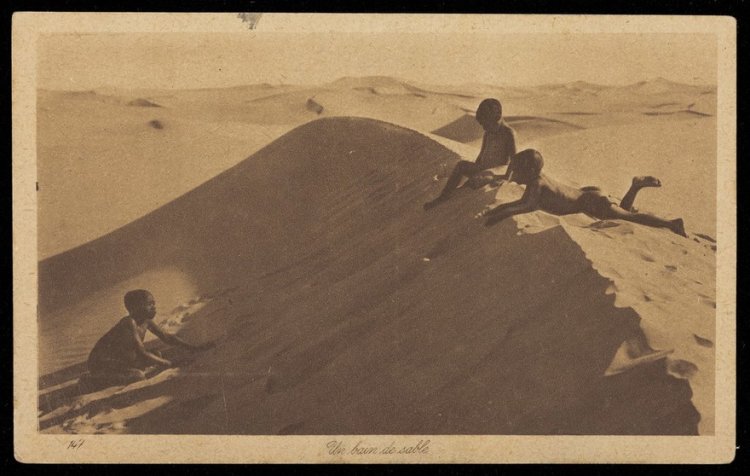

The desert has always held a peculiar grip on the human imagination. It is defined as much by absence as by presence a vast expanse of silence, shifting light and suspended time. For early 20th-century travellers, writers and artists, North Africa and the Sahara promised both solitude and revelation, a glimpse into lives unseen by European eyes. When Rudolf Franz Lehnert and Ernst Heinrich Landrock arrived in Tunis in 1904 with their cameras, they entered not just a landscape, but a powerful visual mythology waiting to be shaped.

Lehnert, a Czech-born photographer trained in art and image-making, brought aesthetic sensitivity and a restless creative eye. Landrock, a German businessman, understood publishing, distribution and the appetite of European audiences. Together, they built a studio that fused artistry with commerce, producing photographs that circulated widely as prints, albums and, most notably, postcards. These images were not neutral records. They helped construct how North Africa was imagined in Europe romantic, timeless and exotic reflecting the desires and assumptions of their audience as much as the realities before the lens.

Lehnert’s photographs ranged from sweeping desert landscapes and village life to carefully staged portraits of women in traditional dress and scenes from the streets of Tunis and Cairo. Landrock ensured these images travelled far beyond the region, turning visual culture into a business. Their popularity was fuelled by the labour-intensive nature of early photography itself. Heavy equipment, fragile glass plates and long exposure times demanded patience and precision. Every photograph was a deliberate act. In today’s era of instant capture and infinite replication, that slowness and craft lend their archive a particular gravity.

By the 1920s, Lehnert & Landrock had relocated to Cairo, where their studio became embedded in the city’s cultural and commercial life. Their reputation grew, even as shifting artistic tastes and the realities of colonial politics complicated how their work was received. During the Second World War, their vast archive of glass-plate negatives was nearly lost when British authorities seized the company due to Landrock’s German nationality. The collection survived only through persistence and circumstance, later reclaimed by Landrock and preserved as a rare visual record of the era.

Today, their legacy endures physically in downtown Cairo, where the oldest foreign-owned bookshop in Africa founded by Landrock still operates. Managed since 1939 by the Lambelet family, Landrock’s descendants, it functions as both a bookshop and gallery, displaying original photographs and glass negatives. Many images have since been digitised, allowing new generations of scholars and viewers to revisit their work.

In 2025, the relevance of Lehnert & Landrock lies not only in history, but in contrast. In an age when smartphones generate thousands of images daily and AI can fabricate deserts, courtyards and markets from a single prompt, their photographs remind us that image-making was once an act of endurance and intention. Craft mattered. Time mattered. The scarcity of images gave them weight.

Yet their legacy is also deeply complicated. Scholars have long noted that Lehnert’s staged portraits particularly of women often reinforced orientalist stereotypes, blurring the line between ethnography and fantasy. Some images veer into voyeurism, constructed to satisfy European expectations rather than document lived realities. To view their archive uncritically would be to ignore the colonial power structures in which it was produced.

This tension is precisely why their work still resonates. Lehnert & Landrock demonstrate that photography has never been neutral. Even at its inception, the camera shaped perception as much as it recorded truth. Their images force us to ask enduring questions: Who is represented? By whom? For what audience? And what is left outside the frame?

In an era dominated by AI-generated imagery and algorithm-driven aesthetics, their photographs serve as both warning and inspiration. They show how images can enchant and mislead, how craftsmanship can elevate even constructed scenes, and how visual narratives can outlast the intentions of their creators.

Once sold as postcards, their works now command significant prices at auction and are treated as cultural artefacts. Commercial imagery has become global heritage. That transformation underscores a central truth about art: its value lies not only in intent, but in endurance.

Lehnert & Landrock’s photographs embody both the achievements and the limitations of their time. They remind us that images carry power, shaped by perspective and consumed through expectation. And in a world where images are infinite and instantaneous, they offer a different model one where patience, craft and deliberate vision gave each frame its lasting weight. That may be their most enduring legacy.